At the dawn of the 20th century, the British Empire deployed one of its most formidable assets—Sikh soldiers from Punjab—to the volatile Chinese port city of Tianjin. Sent to quell the anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion, their presence became a complex and enduring symbol of colonial power. The story of these men is a largely forgotten chapter in Sino-Indian history, revealing a difficult narrative of imperial duty, cultural collision, and a contested legacy that has been obscured by the national histories of both modern China and India.

The deployment of Sikh troops to China was a direct consequence of the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, a violent uprising aimed at expelling all foreign influence. As the international community formed a relief force, Britain drew heavily from the British Indian Army, underpinned by its "martial races" theory. This colonial doctrine designated certain ethnic groups, chief among them the Sikhs, as inherently more warlike and loyal. Valued for their military prowess and intimidating physical presence, Sikh regiments became a key component of the China Field Force. They embarked on a long sea journey to fight in a foreign land for a foreign crown, a reality captured in rare accounts like Thakur Gadadhar Singh’s memoir, Thirteen Months in China, which offers an invaluable Indian perspective on the campaign.

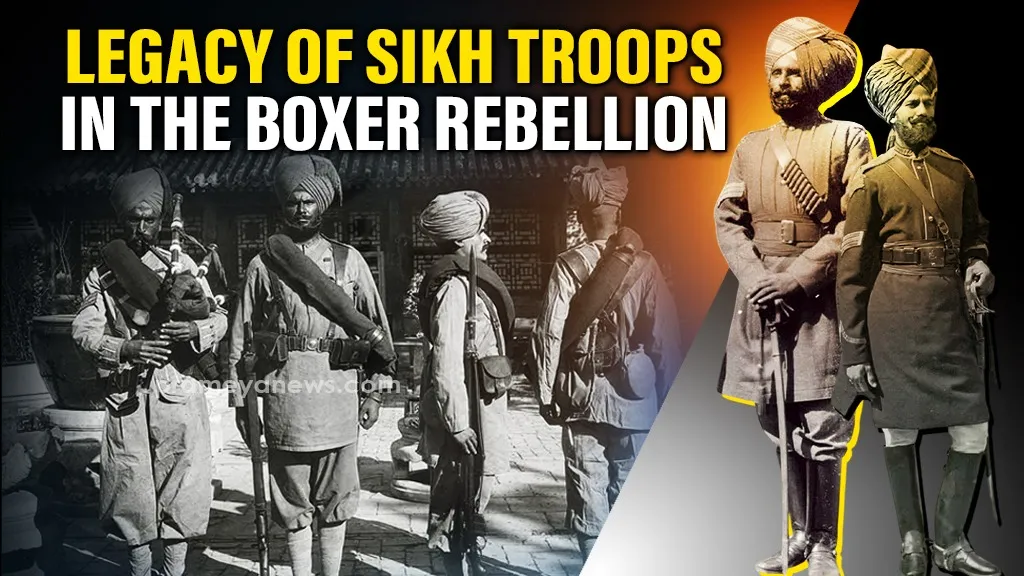

Sikh soldiers proved instrumental in the allied military campaign. They fought with distinction in the brutal, street-to-street combat during the Battle of Tientsin in July 1900, a crucial victory that opened the path to relieving the besieged foreign legations in Beijing. Following the suppression of the rebellion, their role transitioned from combat to occupation. As garrison troops and policemen in Tianjin's British concession, their imposing presence—tall, bearded, and turbaned—was deliberately used as a visible symbol of imperial authority. They guarded key installations, managed city traffic, and became a ubiquitous feature of the colonial landscape, enforcing the order of an empire that was not their own.

The legacy of these soldiers is deeply paradoxical. In the Chinese popular consciousness, they became synonymous with foreign oppression, crystallized in the derogatory nickname Hong Tou A-san ("red-turbaned number three"). This term reflected their perceived low status in the colonial hierarchy and their role as enforcers, a stereotype cemented by their use in suppressing Chinese dissent. Yet, this image of the loyal imperial agent is incomplete. Simultaneously, China became a vital hub for the Ghadar Party, a revolutionary movement of Indian nationalists—many of whom were also Sikhs—working to overthrow British rule. This created an extraordinary situation where Sikh revolutionaries sought to subvert the loyalty of Sikh policemen, who were tasked with suppressing them. This internal conflict reveals a community fractured by the opposing forces of colonialism and nationalism.

Today, the physical and communal traces of this Sikh presence in Tianjin have almost vanished. The community’s spiritual heart, a Gurdwara (Sikh temple) once located in the British concession, has been lost to time and urban development. Likewise, the final resting places of the many soldiers who died and were "buried in Chinese soil" are unmarked and forgotten. This erasure is a consequence of inconvenient historical narratives. For modern China, the Sikh soldier is a reminder of the "Century of Humiliation." For post-independence India, the story of soldiers fighting loyally for the British Empire sits uncomfortably with the celebration of the freedom struggle. Caught between two national histories with no room for their complex role, the story of the Sikh guards of Tianjin has faded into a faint echo of boots on now-unfamiliar streets.