A Decade Under the Lens: Odisha's New Government Probes Outsourcing and Alleged Corruption

In a decisive move signaling a major shift in administrative policy, the new Odisha government under Chief Minister Mohan Majhi has initiated a sweeping investigation into a decade's worth of outsourced government projects. A formal directive has been issued to the Chief Secretary to compile a detailed report on all technical, engineering, and consultancy work awarded to external agencies over the last ten years by key departments. This action has sparked a critical public debate, raising fundamental questions about governance, financial prudence, and a long-standing practice that many believe has systematically favored expensive external firms over Odisha's own capable workforce, hinting at deeper issues of corruption.

The debate, as framed by news analysts, revolves around a powerful analogy: If you have a skilled engineer in your own family, would you hire a costly outsider to build your house? This captures the essence of the controversy. For years, crucial government bodies such as the Works, Rural Development, Water Resources, and Urban Development departments have employed a significant number of qualified engineers and technical staff. This in-house talent pool is equipped to handle essential preliminary work, including project surveys, site investigations, and the preparation of Detailed Project Reports (DPRs). Yet, the practice of outsourcing these very tasks became commonplace, raising questions about its necessity and true cost.

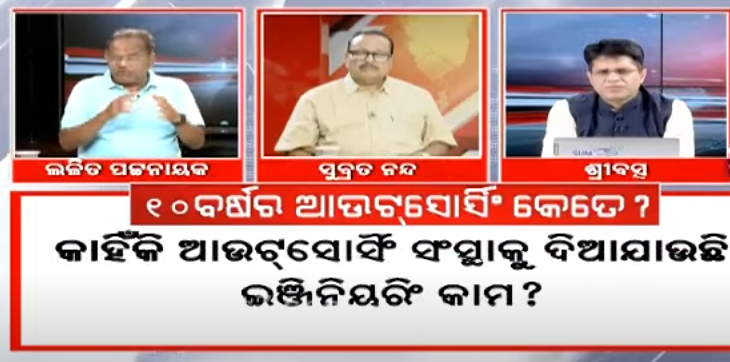

During a televised discussion, experts shed light on the potential motives behind this trend. Engineer Lalit Mohan Patnaik, a panelist, vehemently defended the capabilities of Odisha's engineers, recalling their historic success in executing mega-projects like the Hirakud Dam, Rourkela Steel Plant, and the Rengali Project. He argued that the recent culture of outsourcing even fundamental engineering tasks was a deliberate strategy that not only demotivated government engineers but also served vested interests at the highest levels of the previous administration. According to Patnaik, this approach inflated final project costs by as much as 10-15% and created a system where accountability became diffused, with blame easily shifted to external consultants.

Senior advocate Subrat Nanda expanded on this, describing the outsourcing trend as a systemic "kickback culture" that likely permeated numerous government departments. He asserted that the issue was not a genuine lack of local talent but a lack of political and administrative will to utilize it. By funneling projects to outside agencies, he argued, a corrupt nexus was able to operate with greater opacity. Nanda also highlighted a critical socio-economic fallout: the loss of employment for Odisha’s youth. When projects are outsourced to firms based in other states, the associated job opportunities are effectively exported, leaving local graduates and skilled workers behind. He emphasized that these decisions were often driven from the top down, with ministers and secretaries making calls that bypassed the assessments of their own technical departments.

The Chief Minister’s demand for a ten-year audit is thus being interpreted as more than a routine review; it's a direct challenge to this established and questionable system. The findings of this investigation are eagerly awaited, as they could serve as a turning point. If the probe uncovers significant financial mismanagement and a pattern of deliberately ignoring in-house expertise, it could pave the way for major administrative reforms, stricter accountability protocols, and a renewed policy focus on empowering Odisha's own professional talent. The central question is whether this review will merely document the past or become the catalyst for a more transparent, efficient, and self-reliant future in state governance.