Remembering Jallianwala Bagh 101

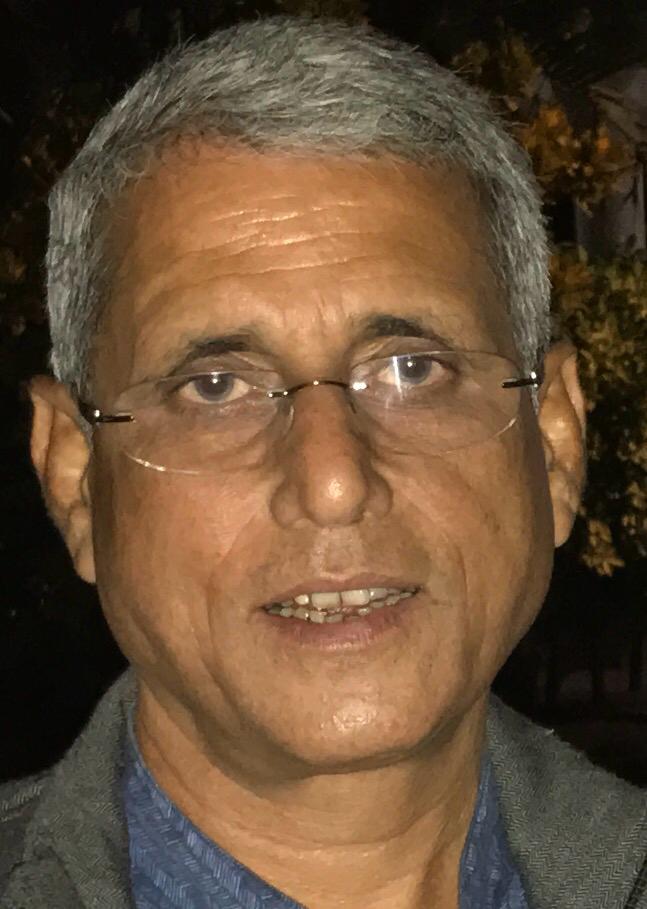

Dr. Mrinal Chatterjee May it never happen. Anywhere.The old lie writhing, bodies riddled with bullet-holes,They are dying; go there, scatter some dry flowersDo all that, you must; but don’t make any noise, stay silentThis is where you mourn; tread gently.(Subhadrakumari Chauhan in her poem Spring In Jallianwala Bagh. Translation from original Hindi by Salil Tripathi) It has often been said that Britain lost its empire the day Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer ordered his regiment of soldiers to fire on unarmed crowd of over 15,000 at an enclosure called Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar, Punjab. The day was 13 April 1919. The firing left 379 people dead and some 12,00 wounded as per official tally. However, the casualty number quoted by the Indian National Congress was more than 1,500, a figure that Civil Surgeon Dr Williams DeeMeddy also corroborated. The massacre ultimately changed the course of history for the British Empire. It was the day of Baisakhi, a particularly holy and festive day for the Punjabis. On this day the ‘Khalsa’ or ‘Pure Sikh Panth’ was founded by Sikh Guru Govind Singh in 1699. The day is celebrated to commemorate this historic and heroic foundation as the Sikh New Year. Besides, the day is important for the farmers as a harvest festival. In early decades of twentieth century the country was in turmoil. Punjab, particularly so. Concerned about rebellious natives, the Rowlatt committee in India had recommended a new law in March 1919, called The Anarchical and Revolutionary Crimes Act. Popularly known as the Rowlatt Act (as it was based on the report of Justice S.A.T. Rowlatt’s committee of 1918), it empowered the state to detain individuals without trial, imposed stricter controls on the press, and permitted warrantless arrests and in-camera trials where the accused would not know the witnesses or the evidence used against them. The passage of the draconian law to curb the protests against the government precipitated large scale political unrest throughout India. Mahatma Gandhi’s call for protest against the Rowlatt Act achieved an unprecedented response of furious unrest. The law and order situation of Punjab was deteriorating rapidly, with disruptions of rail, telegraph and communication systems. The movement was at its peak before the end of the first week of April 1919. On 10 April 1919, there was a protest at the residence of the Deputy Commissioner of Amritsar. The demonstration was to demand the release of two popular leaders of the Indian Independence Movement, Satya Pal and Saifuddin Kitchlew, who had been earlier arrested by the government and moved to a secret location. Both were proponents of the Satyagraha movement led by Gandhi. The violence continued to escalate, culminating in the deaths of at least five Europeans including government employees and civilians. By 13 April 1919, the British government had decided to put most of the Punjab under martial law. The legislation restricted a number of civil liberties, including freedom of assembly; gatherings of more than four people were banned. On the evening of 12 April, the leaders of the hartal in Amritsar held a meeting at the Hindu College. It was announced that a public protest meeting would be held at 16:30 the following day in the Jallianwala Bagh. By mid-afternoon, thousands of people- Sikhs, Muslims and Hindus- men women and children- had gathered at the Jallianwala Bagh (garden) near the Harmandir Sahib (Golden Temple) in Amritsar. The Jallianwala Bagh was surrounded on all sides by houses and buildings and had few narrow entrances. Most of them were kept permanently locked. The main entrance was relatively wide. Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer arrived with his regiment of 50 Gurkha and Baluchi riflemen. He had brought two armoured vehicles with mounted machine guns. But these could not enter through the gate. Without warning the crowd to disperse—the main exits were blocked. Dyer ‘explained’ later that this act “was not to disperse the meeting but to punish the Indians for disobedience.” He ordered his troops to begin shooting toward the densest sections of the crowd. Firing continued for approximately ten minutes till the soldiers almost ran out of ammunition. Approximately 1,650 rounds were fired. Besides bullet wound, many people died in stampedes at the narrow gates or by jumping into the solitary well on the compound to escape the shooting.The scale and barbarity of violence shocked the nation- as and when the news travelled to its nook and corner, mostly through word of mouth as strict restrictions of press had been imposed. However, there were some journalists and editors who did disseminate this news - at a great risk. Consider how strictly the news was suppressed in the fact that details of the massacre did not become known in Britain until December 1919. The reaction of the political parties in India was slow to come. Rabindranath Tagore received the news of the massacre by 22 May 1919. He tried to arrange a protest meeting in Calcutta and finally decided to renounce his British knighthood as “a symbolic act of protest”. On 14 October 1919, after orders issued by the Secretary of State for India, Edwin Montagu, the Government of India announced the formation of a committee of inquiry into the events in Punjab. Referred to as the Disorders Inquiry Committee, it was later more widely known as the Hunter Commission, named after the chairman, William, Lord Hunter, former Solicitor-General for Scotland and Senator of the College of Justice in Scotland. Though the political leaders were ‘slow’ to react to the massacre, it triggered a reaction among the masses of the country. It united them in demanding the ouster of the alien government. The British continued to govern India for 28 years after the Jallianwala Bagh tragedy. But 13 April 1919 was the beginning of the end of the British Empire. It took less than two decades for the empire to collapse. wp:separator /wp:separator The author works as Professor and Regional Director of Indian Institute of Mass Communication (IIMC), Dhenkanal, which has published a monograph: ‘Jallianwala Bagh 101: Retrospect’ to commemorate the 101 years of the tragedy. If you want an electronic copy of the monograph send an email to [email protected]

Latest News

Rising cases of pediatric liver issues linked...

Odisha reports first sunstroke death, seven pl...

Junior Revenue Assistant dismissed from govt....

Dell launches AI-powered laptops, mobile works...

IPL 2024: Lucknow test await CSK at Ekana Sadi...

Sanjeeda Shaikh dazzles as Waheeda in 'Heerama...

BEO office Senior Clerk held for accepting bri...

Copyright © 2024 - Summa Real Media Private Limited. All Rights Reserved.